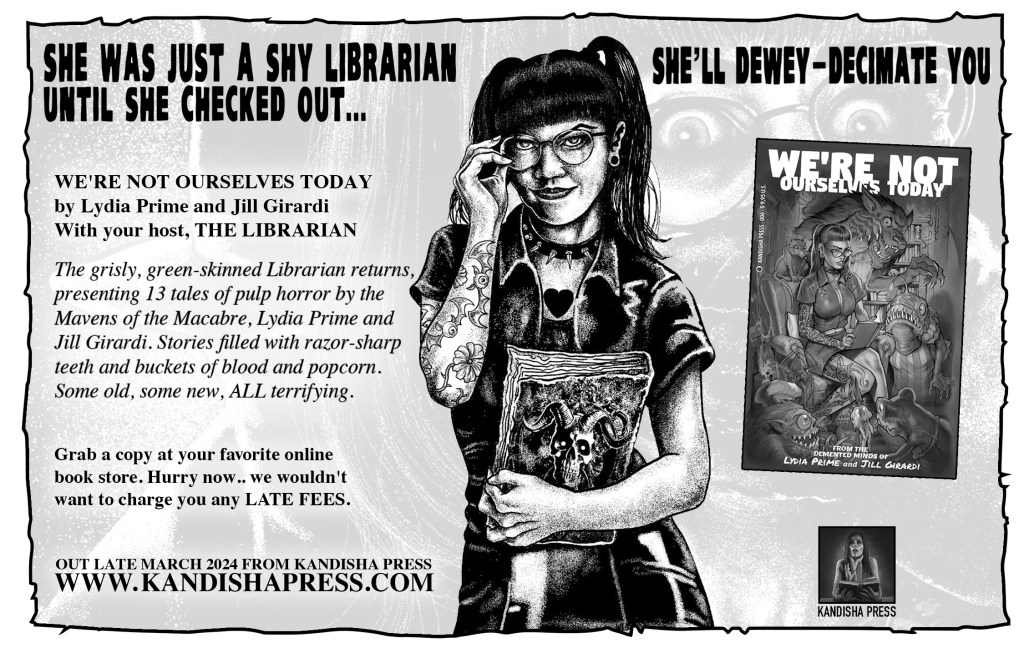

GREETINGS, BOOKWORMS! I’m Aisha Kandisha, Head Librarian at Kandisha Press. Join me in the dusty stacks of the library I will never leave again as I chat with some of my favorite Women in Horror. Today we feature author Lee Murray!

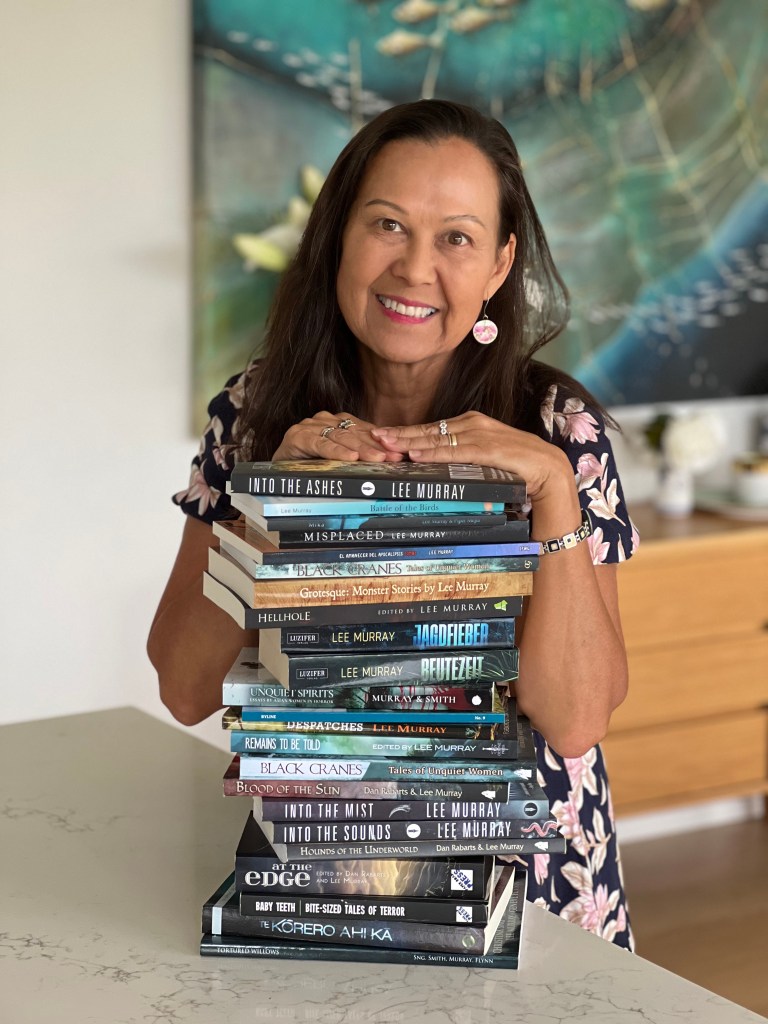

Lee Murray is a writer, editor, poet, and screenwriter from Aotearoa. A USA Today Bestselling author, her titles include the Taine McKenna Adventures, supernatural crime-noir series The Path of Ra (with Dan Rabarts), fiction collection Grotesque: Monster Stories, and several books for children. Her many anthologies include Hellhole, Black Cranes (with Geneve Flynn), and Unquiet Spirits (with Angela Yuriko Smith), and her short fiction appears in Weird Tales, Space & Time, and Grimdark Magazine. A multiple Bram Stoker®-, Australian Shadows-, and Sir Julius Vogel Award-winner, Lee is New Zealand’s only Shirley Jackson Award winner. Recipient of a prestigious New Zealand’s Prime Minister’s Award for Literary Achievement, Lee is also an NZSA Honorary Literary Fellow, a Grimshaw Sargeson Fellow, and the 2023 NZSA Laura Solomon Cuba Press Prize winner. Read more at leemurray.info

What made you want to become an author? Did you have an “Aha!” moment when you knew you were born to write? Or perhaps a beloved book inspired you?

Looking back, I think it was my dad’s idea rather than purely my own. Throughout my childhood, he always seemed to be gearing me up to be a writer. Infusing me with a love of story. Reading to me. Encouraging me to play with language. He was a great storyteller himself with quiver of fabulous tales to share or he would simply make them up on the spot. When you have four kids under six and not a lot of money, you have to find your entertainment where you can. From my earliest memories, part of my bedtime ritual was to hear a made-up story by my dad, complete with all the wonderful voices. My favourite of his characters were two little frogs, and a back-shed inventor called Professor Morgan, who was a bit of a cartoon version of himself. Dad’s characters were unassuming but full of derring-do, the sort who were willing to give it a go in order to help out a friend. Somehow, despite their bumbling, they always managed to conjure a brilliant off-beat idea to overcome the obstacle and save the day. When we would take weekend trips to the capital to see family, a drive of some seven hours, Dad would regale us with a shaggy dog story involving a cousin or a neighbour who had arrived too late to join us in the car and were now running just a few steps behind us, desperately trying to catch up, and all the while the cousin or neighbour would be jumping fences, tripping in cow poo (we loved that one), running through farmhouses and so on. We used to join in, scanning the landscape for interesting calamities to add to the story. So I was always interested in stories, always reading, always scribbling down tales—usually long-winded ones with lots of hurdles to navigate. I remember being twelve or maybe thirteen, and running into the kitchen, book in hand, and declaring that I was going to be novelist; I’d just finished reading Gone with the Wind. So perhaps that book was the catalyst. Later though, when it came time to choose a career, Dad changed his tune. A child of the depression, he knew the arts were precarious, so he encouraged me to get a ‘real job’. (And by this he meant be a doctor.) “There’s no money in writing,” he said. So I went off to university, got a few degrees, and became a research scientist. Only my love of story never faded, and still later, in my forties, I turned again to writing, this time with some life experience and two children of my own.

What I didn’t realise until much later still was that all that time I’d thought Dad had simply been keeping me entertained, he had, in fact been teaching me the basic principles of storytelling. About giving your characters purpose and agency, and then challenging the core beliefs of your protagonist by throwing everything at them. He taught me to put myself in the story, to draw in the audience with a compelling hook, and to use landscape and setting to good effect. To give my characters distinct voices. And how to leave them hanging upside-down from the washing line until tomorrow night. Dad showed me how to to have fun with narrative and perhaps it was that early playfulness that drew me in.

And then, later, I discovered the darkness…

What do you believe are your strengths in writing? And when you feel you need to improve on a particular writing skill, how do you go about it?

This is a tricky question because despite being immersed in story all my life, when it comes to putting words on the page, I’m not a natural writer and nor am I particularly fast, barely making 500 words per day. Fiction has to be dragged kicking and screaming out of my brain, and even then, I’m never satisfied with it, writing and rewriting, and generally overthinking it. Plus, I suffer from a good dose of imposter syndrome, which complicates things. So perhaps my best skill is persevering in a discipline that doesn’t come naturally to me.

With regards to the technical aspects of writing, by the time I finally gave myself permission to write, I’d read dozens of books on the craft of writing. However, I still lacked confidence, so I did some graduate courses in novel writing which gave me access to peer support and specific input from more experienced writers. Beyond that, I developed my skills ‘sur le tas’, attending weekend workshops and courses, and conferences and panel events, joining writing groups, and critiquing my colleagues’ work. I still do those things. I’m of the school that if you think you’ve learned everything there is to know, then you may as well give up. If you’re not still challenging yourself, not still evolving and striving to write imaginative, innovative fiction, then why continue? While I understand that the publishing industry is focused on the product, for me, writing is about art and creativity.

If I’m truly honest, I’m more of a natural editor than an author, probably the result of all that writing and rewriting I mentioned. Perhaps it’s the scientist in me hungering for rigour and clarity. Or it’s the anxious-piglet aspect of my nature, that tendency to overthink that I can apply to other people’s work, my excess nervous energy burned up considering how they might improve the clarity and effectiveness of their writing. It’s always a privilege to be entrusted with a colleague’s work, being asked to help shape it, to offer the insight and objectivity that will allow them to polish the piece without losing their intent, meaning, or voice. It’s a bit like being asked to add a shake of pepper to a carbonara to lift the dish before it is served. Mostly, I love the community that curating and editing an anthology entails, the opportunity to connect with writers, editors, and publishers, some of whom have become lifelong friends.

What are your thoughts on the book industry today, or more importantly, about the book community? Do you feel it is getting harder or easier to make it as an independent author these days?

Being a New Zealand writer, and particularly an Aotearoa writer of speculative fiction and horror, the traditional book industry is particularly difficult to access. There is little interest in supporting the development of genre work from local funding agencies, and our current government has been making determined noises about cutting funding to the arts, which will make access to that limited support even more difficult. As far as traditional publishing goes, a couple of the Big 5 houses exist here, but none of those are open to speculative work, or their presence here is primarily to bring international titles into the country rather than to commission and acquire local work to distribute elsewhere, and in fact territorial contracts often preclude local work from access to worldwide readerships. I can count the New Zealand literary agencies on one hand and still have some fingers left over. The cost of printing and shipping books is prohibitive—we’re stuck out here at the end of the world, after all—plus, our booksellers are retrenching; those that remain aren’t particularly interested in stocking self-published or independent works. Another issue is that New Zealanders tend to read non-fiction. I read some stats somewhere that said less than 5% of all books sold in New Zealand are fiction, and that includes children’s books. And there is a cringe factor that is associated with home-grown work. Don’t even get me started on attitudes to horror by readers, festival organisers, and local media. My own career has been a mix of traditional publishing (almost entirely with small press) as well as some self-published titles, and with no literary representation, so every commission or sale feels like a win. Any exposure to overseas markets has been at my own expense since the cost of travel to and from New Zealand makes conference organisers pale in shock and back away quickly. But Aotearoa is founded on intrepid, resourceful, resilient pioneers. Down here, we call it Number 8 Wire mentality, which means Kiwis are used to making things work with very little and even when the odds are enormous. So into this environment there is a flourishing community of independent writers and artists who are leaping barriers to find new ways to get their work into the world, even with the threat to creative work posed by AI tools, I am hopeful for New Zealand fiction in general.

Tell us about your work. What story are you most proud of?

I’m proud of all my stories. Yes, sometimes I cringe a little when I think about the early ones, because, obviously, there are some things I would change now with the benefit of hindsight and experience. The thing is, as a writer I am always striving to grow and do better. To tell stories in new and engaging ways so they resonate for readers. I’m always looking to address current issues in ways which offer new insight. That’s why, when people ask me what my favourite story is, I always say it is the next one. The one I’m working on now.

What are your upcoming works and plans for the future?

Thank you for asking! I’m thrilled to say that Fox Spirit on a Distant Cloud, my first solo prose-poetry collection (or novel in prose), is scheduled to release on 1 April of this year from The Cuba Press (NZ). This project is very personal and very dark. Here’s is what my colleague Yi Izzy Yu has to say:

“In this luminously transcendent page-turner, Murray proves herself a deftly magical storyteller, one equally adept at rendering savagery and revelation. This daring fusion of archival history, Chinese fantasy, and poetic invention will stun the reader like a divine revelation and haunt them like their own strange and unforgettable dream.” —Yi Izzy Yu, acclaimed author of The Shadow Book of Ji Yun

Inspired by my work with Geneve Flynn on the award-winning anthology Black Cranes, and later with Angela Yuriko Smith, Christina Sng, and Geneve Flynn on poetry collection Tortured Willows, Fox Spirit on a Distant Cloud examines the lives of Chinese diaspora women in Aotearoa (Māori: land of the long white cloud) through the lens of the shapeshifting fox spirit of Asian mythology. The project was kindly supported by a fellowship from the Grimshaw Sargeson Trust, and the completed manuscript went on win the 2023 NZSA Laura Solomon Cuba Press Prize for unique and innovative writing. I can’t wait to share the book with everyone when it comes out next month.

Here is the back cover text:

Wellington, 1923, and a sixty-year-old woman hangs herself in a scullery; ten years later another woman ‘falls’ from the second floor of a Taranaki tobacconist; soon afterwards a young mother in Taumarunui slices the throat of her newborn with a cleaver. All are women of the Chinese diaspora, who came to Aotearoa for a new life and suffered isolation and prejudice in silence. Chinese Pākehā writer Lee Murray has taken the nine-tailed fox spirit húli jīng as her narrator to inhabit the skulls of these women and others like them and tell their stories. Fox Spirit on a Distant Cloud is an audacious blend of biography, mythology, horror and poetry that transcends genre to illuminate lives in the shadowlands of our history.

Thanks so much for having me.